Here's the original article from the California magazine May 1983 issue, presented as a tribute to author Ehud Yonay. This article and these photos inspired the Paramount motion picture "Top Gun." Think back to the days before the movie, before GoPro cameras and squadron videos on YouTube ... Yonay took readers into the cockpit with incredibly vivid descriptions. Be sure to read his sidebar at the bottom of the page, in which he finally got his own dogfight hop.

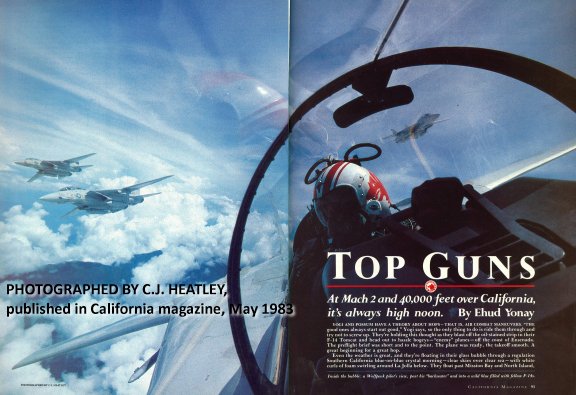

Inside the bubble: a Wolfpack pilot’s view, past his “backseater” and into a wild blue filled with fellow F-14s. PHOTOGRAPHED BY C.J. HEATLEY.

Inside the bubble: a Wolfpack pilot’s view, past his “backseater” and into a wild blue filled with fellow F-14s. PHOTOGRAPHED BY C.J. HEATLEY.

Top Guns – by Ehud Yonay

California Magazine, May 1983

At Mach 2 and 40,000 feet over California, it’s always high noon.

Yogi and Possum have a theory about hops – that is, air combat maneuvers. “The good ones always start out good,” Yogi says, so the only thing to do is ride them through and try not to screw up. They’re holding this thought as they blast off the oil-stained strip in their F-14 Tomcat and head out to hassle bogeys – “enemy” planes – off the coast of Ensenada. The preflight brief was short and to the point. The plane was ready, the takeoff smooth. A great beginning for a great hop.

Even the weather is great, and they’re floating in their glass bubble through a regulation Southern California blue-on-blue crystal morning – clear skies over clear sea – with white curls of foam swirling around La Jolla below. They float past Mission Bay and North Island, then Possum calls out a new heading and Yogi hangs left, and they're making straight for today's action.

Once over the Mexican border they pick up speed, and Yogi starts jinking. He whips the stick - the steering mechanism between his legs – from side to side and the plane rolls this way and that, letting him and Possum spot anybody making for their tail. From where they sit, however, it's not their silver rocket that's rocking but the entire vast blue dome of sea and sky. There are no ups or downs up here, no rights or lefts, just a barely perceptible line separating one blue from another, and that line is spinning and racing like mad in the distance. Yogi was still in junior high school when he realized that flying straight and level might be okay for some people, but if you like yanking and banking- the feeling of riding inside one of those storm-in-a-bottle souvenirs - then there's just one place for you, and that's the cockpit of a fighter plane.

They're at just about the right spot, over international waters some 30 miles off Ensenada, when a voice crackles over the radio to warn of two bogeys 20 miles south.

"Fight's on," says Yogi, who is the pilot, or "stick," and sits up front.

"Roger," says Possum, the radar intercept officer, or "backseater." He's already bent over his radarscope, punching buttons and looking for the tiny blips of the bogeys - hotshot instructors from Top Gun, the Navy Fighter Weapons School, flying their deadly little F-5s.

With that, Yogi stops jinking, peels off to the right, and pushes the throttle all the way into afterburner. As twin white-hot flames shoot out from the plane's exhaust nozzles, the magnificent silver machine explodes forward, slamming into their backs like a truckload of bricks and hurling them through the sound barrier. Yogi has rehearsed this kill in his mind a dozen times. He'll cut the first bogey off at the pass with a head-on missile shot, and then, breaking and rolling to avoid getting hit, he'll rein the plane in and pull it around like Ivanhoe at the end of the first joust and come racing back across the skies for the other. Great fighter pilots are always ahead of their planes, and, as his adrenaline surges up, Yogi's eyes bore into the empty blue space before him, looking for the bogeys. Nothing can stop him now.

That's when it happens. Suddenly a soft voice is saying "Atoll" in the earphones, and by the time Possum spots the little F-5 behind them it's too late. They've been racing fat and dumb and happy like a dodo bird, and the F-5 painted in desert camouflage, no less, which stands out against the blue like a billboard - just rolled in out of nowhere, got on their tail, and simulated slipping a heat-seeking missile up their exhaust pipe. Atolls are the air-to-air missiles that Russian-built MiG-21s carry, but in this exercise the word means, "Up yours, guys, you're dead and going home with your tail between your afterburners." Their glorious hop is all screwed up.

"I was just starting to transition from my visual scan aft to forward, and Possum's visual scan from inside to outside, and we're dead," says Yogi, who is 26 years old and has the gangly good looks of a John Travolta, in amazed indignation. That's pilot talk for driving without looking. "It started out good, but it sure got bad in a hurry," Possum says, laughing. He is 25 and more the Ryan O'Neal type, with brown hair and mustache. "You wish you could do it over again," he says, "but in the real world you're not going to get a second chance."

It is evening, and the briefing room is quiet. There is a faint aroma of sweat and boot polish and jet fuel in the air. Everybody has left the hangar to bend elbows and play video games and talk great hops at the officers club, but Yogi and Possum stay behind, slouching at their desks in their black flight boots and green flight suits with red turtlenecks showing. They can think of any number of other hops they'd rather talk about. Good hops. "In this business you hate to lose," Yogi says, "and getting shot is synonymous with losing -- getting your parachute and dying and all that sort of thing." He walks to the blackboard and picks up a couple of fighter plane models. Holding the F-14 straight and level in his left hand, he raises the little F-5 with his right and rolls it down behind the F-14, describing what happened. "You feel just like kicking yourself in the butt," Possum says.

What makes this particular screw-up even worse is that Yogi and Possum are not with their regular squadron, the VF-1 Wolfpack based at Naval Air Station Miramar in San Diego County. For the last two weeks they've been training at Top Gun, Miramar's internationally known Navy Fighter Weapons School. Just getting here was the ultimate break. Only the best young flyers in a squadron ever make it, and they have already raced past most fighter pilots their age. If they play it right and look sharp, they might even get invited back as Top Gun instructors -- which is as high as a fighter pilot can get.

And now they have only three weeks left to make it up. "All you can do at this point is make sure that no wild card ever, ever jumps on your tail again," Possum says.

Yogi shrugs. "It's Miller time," he says, hanging up the little model planes, and they head out into the night.

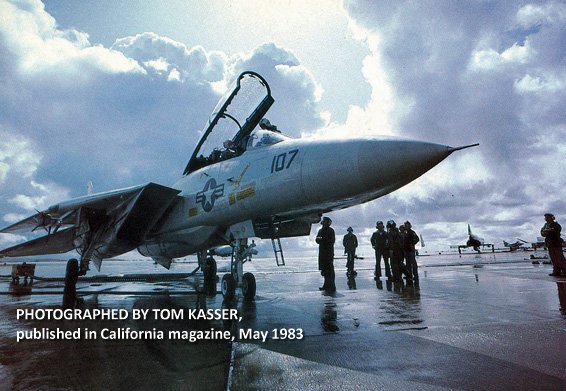

Yogi (the pilot, right) and Possum (his radar intercept officer) strap themselves into the cockpit of their F-14 before blasting off into broken San Diego skies. PHOTOGRAPHED BY TOM KASSER.

Yogi (the pilot, right) and Possum (his radar intercept officer) strap themselves into the cockpit of their F-14 before blasting off into broken San Diego skies. PHOTOGRAPHED BY TOM KASSER.

WHEN YOGI AND POSSUM return from a hop and fly into Naval Air Station Miramar, the first thing they see at the end of the runway is a huge red sign stenciled the length of a low, 300-foot-Iong building: WELCOME TO FIGHTERTOWN, U.S.A. Though the call sign of Miramar is "Home of the Pacific Fleet Fighters," Fightertown is handier and far more appropriate, since the entire mission of this sprawling 24,000-acre base - wedged inside a fork formed as I-15 and I-805 cross diagonally some fifteen miles north of San Diego - is to primp and fuss over several hundred fighter jocks so that when the time comes and they're staring down the missile racks of a Russian MiG, they are primed and ready.

Lieutenants Alex ("Yogi") Hnarakis and Dave ("Possum") Cully are what naval lingo terms a "crew," or an F-14 team. There are twelve crews in each fighter squadron - in their case, the VF-1 Wolfpack - and there are a dozen such squadrons stationed at Miramar, home base of all the fighter squadrons assigned to the U. S. Pacific Fleet. In "our" half of the world, starting at the California coast and stretching west to the tip of Africa, the Pacific Fleet maintains two battle groups in constant readiness, one in the Indian Ocean and the other in the Pacific. Bigger than many small nations' entire navies, each battle group - consisting of some half dozen guided missile cruisers, two dozen or so destroyers and frigates, and an aircraft carrier equipped with various early-warning, submarine- patrol, and attack planes - is, in effect, a floating hunk of American territory that can carry a battle to the enemy's doorstep, thus keeping it from our own. But these armed flotillas are sitting ducks. In the Falkland Islands last summer, all it took was one Exocet missile from a plain-vanilla Super Etendard Argentinian (sic) plane to sink the destroyer HMS Sheffield, pride of the British Navy. No matter how big the ship or how long its cannons, it is helpless without the assurance of "air superiority" over the battlefield.

That's where fighter pilots such as Yogi and Possum figure in. Aboard each carrier are two F-14 fighter squadrons whose job is not only to protect the battle group against air attacks but to ride shotgun over the carrier's three squadrons of attack planes as they go about their bombing and strafing sorties into enemy territory - what the navy calls "power projection." This is the anachronism of fighter aviation. Even in this age of remote-control, pushbutton warfare, the survival and effectiveness of the entire U.S. Pacific Fleet rests on a few dozen young men getting themselves catapulted off a flight deck and hanging it in the skies against numerically superior, land-based enemy planes.

"It's like in the old days," says Commander Jack ("Gringo") Snyder, leader of the Wolfpack, "when one knight from each side would come out and they'd joust, one on a white horse and one on a black horse." Tall and wiry, which comes from doing 200 push-ups and 100 sit-ups a day in preparation for the joust, Gringo flew an F-4 Phantom in the Vietnam War. He knows that even the greatest air battle is a series of individual duels - that, while a dozen pilots may blast off a carrier at one time, once they get up there they are alone, hurtling through enemy air at 750 miles an hour and tilting against tiny motes of silver that zoom out of the blue to become fire-spitting machines.

Which is where keeping bogeys off your tail and that little hop off the coast of Ensenada come in. "You fight like you train, so you'd better train like you're going to fight," fighter pilots like to say. It is also where Top Gun comes in. If Miramar is a fighter pilot's Camelot, then the Top Gun complex in Miramar's Hangar Number One is King Arthur's Round Table, the gathering of the greatest of the greats in fighter aviation. Since its inception in 1968, Top Gun's hotshot aces have virtually revolutionized the fighter pilot business and, with the possible exception of the Israeli Air Force, established themselves as the international masters of the deadly art of air-to-air combat.

Like the notion of the single-combat warrior, there is something slightly nostalgic about Naval Air Station Miramar. At night the darkened base could be mistaken for an old From Here to Eternity set, and even earlier in the day, when the base is bustling, it is enveloped in a time warp of unreality. Not just because it looks like a small desert town out of the 1950s - tract houses, a supermarket, a Baskin-Robbins ice cream parlor, a golf course, and a bowling alley complete with a Lucky Strike Tavern and Ten Pin Cafe - but because it has no real reason for being here. The only centers of activity, activity that matters, are the stretches of runway at the south end and the officers club at the north. If an earthquake struck tomorrow and shook everything off the base except the flight line and the O club, few pilots would know the difference.

Among the fighter pilots at Miramar, "officers club" does not refer to the sprawling complex of dining rooms and meeting halls, but rather to the small space at the heart of the building that begins in a vestibule covered from floor to ceiling with heavily carved wooden plaques - more like coats of arms - of the various squadrons. This is the entrance to the WOXOF Room, the inner sanctum of Miramar's knightly order. (In aviation circles the letters and zeros in WOXOF refer to various unfavorable weather conditions- X means "obscured," for example, and F means "fog" - and strung together the letters mean, "You're grounded, why not make the best of it?") Inside, the walls are hung with more squadron emblems, and there are glowing Zaxxon and Donkey Kong video games and a small stage lit in reds and greens where, this evening, two young and zesty girls in bikinis are disco dancing.

It is the Wednesday night happy hour, and the small, noisy room is packed with pumped-up fighter jocks. There is a lively trade at the bar, mostly in light beer, but out of this crowd of 50 or so men no more than 3 are looking at the nearly nude dancers. With raw sex waving right in front of their eyes, these supremely healthy young males are standing around in twos and threes and talking about the hop. You don't even have to listen to catch on - just watch their hands tracing loops and rolls and aerial ambushes with the grace of a ballerina's.

Lieutenant Commander C.J. ("Heater") Heatley is one of the Wolfpack's top F-14 drivers. Tall and boyish, with curly brown hair and quiet blue eyes, Heater likes to think things out, such as the reason fighter pilots hang together and "shoot off their watches" in the WOXOF Room. They do it, he says, for the same reason stunt men or Joseph Wambaugh's cops or anybody else who hangs it out there for a living heads for a bar after a day's work. "You're out there supersonic going from deck to 40,000 feet and back down to the deck, simulating killing people and getting yourself killed, handling actual emergencies, and when you finally come in and land you can't even tell your wife about it," he says. "How do you explain 6.5 Gs [six and a half times the force of gravity] - that you're sitting there and you weigh 200 pounds, but when you turn for that bad guy you suddenly weigh more than 1,300? Or how if you pull too many Gs a lot of times you start to black out, and how do you explain that you were in an airplane flying around and you blacked out?"

So that's the torture. But what about the good things?

Heater throws up his hands. He knew it was pointless even to try to explain. "But those are the good things," he says. "That's not torture, that's good. I like pulling Gs. I like strapping on 25 tons of airplane and hustling around the sky. I like that."

So that's where it all starts. With the love of flying.

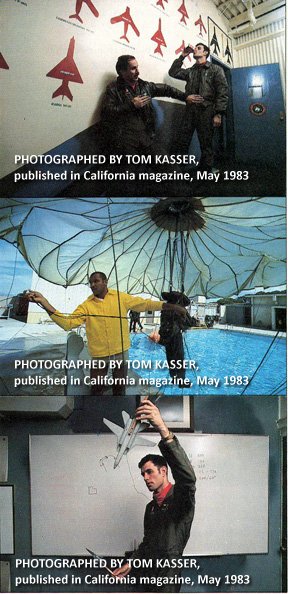

Possum (left) and Yogi take a break at Miramar's Hangar Number One. On the walls are silhouettes of MiGs shot down in combat by Top Gun graduates. Center: The water survival course prepares young pilots for bail-outs over the ocean. Bottom: Yogi describes a hop in the briefing room. PHOTOGRAPHED BY TOM KASSER.

Possum (left) and Yogi take a break at Miramar's Hangar Number One. On the walls are silhouettes of MiGs shot down in combat by Top Gun graduates. Center: The water survival course prepares young pilots for bail-outs over the ocean. Bottom: Yogi describes a hop in the briefing room. PHOTOGRAPHED BY TOM KASSER.

ALEX HNARAKIS WANTED TO FLY ever since he was twelve, when in 1968 he sat in front of the TV at his parents' home in the suburbs of Washington, D.C., and watched the Apollo 8 astronauts flying around the moon. So once out of high school he cut off his long hair, shaved his beard, and entered the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. There was a small flying school at a nearby civilian airport, and in his senior year he logged a few solo hours - it wasn't military flying, of course, more like putt-putting around inside a lawn mower with wings, but it was better than nothing. He graduated in 1978, six months before his flight training was to start, and was put on temporary duty with VF-111 squadron at Miramar, which was just switching from F-4 Phantoms to awesome F-14 Tomcats. Suddenly he was hanging out with real fighter pilots, sitting in on real briefings, and even hitching rides in the backseat of an A-4 Skyhawk, getting bumped and bounced and breathless pulling Gs. It blew his mind, he remembers, but there was an admission price to this land of the giants. "I had to do well in flight school," Yogi says, "because only by being at the top of the Class could I get my choice of flying fighters, and get to fly F-14s." In September 1980 he finished flight school at the top of his class and, with his new gold wings glistening on his tropical khakis, headed for VF-124 squadron at Miramar.

Dave Cully was born in Detroit and grew up in Newport Beach. He wanted to fly, too - just like his older brother, an army helicopter pilot in Vietnam - but his brother told him to be smart, to go to college and take ROTC on the side. He entered UCLA in 1975, played ice hockey and lacrosse, and in June 1979 graduated as an officer with a degree in economics. He already knew he couldn't be a pilot. His eyes weren't good enough. But navy fighter planes have two-man cockpits, and the sight requirements for backseaters aren't as strict. "It was like, there were the cards, and I could take my hand or walk out," Possum says. "But I wanted to fly." He was "stashed" on temporary duty at the Navy Fighter Weapons School at Miramar. In the summer of 1980 he came out of flight school with his Naval Flight Officer wings, married his high school sweetheart, and was assigned to VF-124. That's where Yogi and Possum met, while learning to fly F-14s.

Yogi had flown jets in flight school – the T-2 Buckeye and A-4 Skyhawk – but moving up to the F-14 Tomcat meant crossing the magic line that separates the men from the boys, like first-time sex, glorious and terrifying. The difference is the afterburner, an engine component that at the pull of a throttle begins to burn huge amounts of fuel at incredible speed, resulting in a burst of power that no ordinary jet engine can duplicate and no plane but a fighter ever needs. “Just getting into an afterburning aircraft is a sensation most attack guys will never know that feeling of power,” says Lieutenant Rick ("Organ") Hammond, a member of the Top Gun squadron. "The first time I lit the afterburner in an F-14, the airplane just, you know, just literally moved."

The F-14 Tomcat is the U.S. Navy's supreme air war machine, a huge, luxurious monster that could have been designed by the Star Wars special effects crew. Its wings can sweep back for fast flying or open to the sides like an eagle's for landing or just for cruising around-"loitering" in navy jargon. It can shoot up to 30,000 feet in one minute, fly at more than twice the speed of sound, and haul seven tons of guns and missiles - including the heatseeking Sidewinder, the radar-guided, mid-range Sparrow, and as many as six Phoenix missiles, half-ton monsters that can home in on a bomber more than 100 miles away. In fact, the F-14's radar system can track 24 targets at once and fire six missiles in six different directions in rapid sequence. By comparison, the much smaller Russian MiG carries little more than guns and a few missiles, and must get quite close to a target - directly behind in order to use its heat-seeking Atolls - to hit it.

But the F-14 does have its drawbacks. The plane's enormous size is a disadvantage (it can be seen as far away as ten miles), and it is so technically complex that it takes between 20 and 25 hours of work by ground crews to keep it flying for just one hour. The biggest problem, however, is the F-14's price. The next batch of Tomcats to roll off the Grumman Aerospace assembly line on Long Island will cost $36 million apiece, which doesn't leave much for an adequate stock of spare parts or for new replacements for the plane's troublesome TF-30 engines. The TF-30s "have been, over the years, on a comparative basis, stall-prone," says Rear Admiral George M. ("Tiger One") Furlong Jr., commander of the Pacific Fleet fighter squadrons. At high angles of flight, not enough air flows into the engines, and they die - and in very rare instances the only way to restart an F-14 in the air is to point it nose down and dive until the airflow 'starts the fans going.

The F-14 has been plagued with other technical troubles since its introduction in 1972, and in 1976 a deadly streak of accidents swept Miramar, killing four men in one 48-hour period alone. That none of these accidents dampened the pilots' enthusiasm for the plane is just another clue to the fighter pilot's code. "They have an incredible denial mechanism," says Captain R.A. Millington, flight surgeon for the Pacific Fleet's aircrews. When an aviator dies, his picture is removed from the squadron roster, his locker emptied of his personal belongings, and all other traces of his presence on the base are obliterated. Even accident reports that clearly demonstrate technical failures don't erase the lingering doubt. "You think there must have been something he could have done and didn't - that if it were you it wouldn't have happened," Heater says. "Such planes take off and land every day without accidents, so obviously it can be done."

It takes nine months to learn how it is done. You start by spending hours and even days in flight simulators that cost as much as real planes but can't crash and don't use gasoline (you can train an hour a day for a whole week in a simulator for what it would cost to fly 60 minutes in an F-14, which burns $1,500 an hour in gas alone). Some of the simulators are simple - a cockpit with a small screen in front - but once you master the basics you're ready for the highest high-tech high, the 2F-112, the world's ultimate video game.

You don't just sit and play the 2F-112, you walk into it like an H.G. Wells traveler stepping into the time machine. You and your radar intercept officer climb up and strap into an F-14 cockpit mounted twenty feet high, at the center of a 40-foot-diameter spherical room. The lights go off, and suddenly the entire dome becomes the great outdoors. The illusion of flying is total – move the stick and the scenery moves in response, rolling and soaring and falling. The real action begins as the bogeys start coming at you, and you pull and push and twist the stick, trying to keep them off your tail and get onto theirs instead. Screw up and you go into a spin, and if you don't make the right moves to pull out of it, you crash. The room goes black.

Simulator flights are followed by real flights-low and high, formation flights and air combat maneuvers - and finally, by the last month of training, there's one thing left to do before you join your permanent operational squadron. It is something so awful, so mortifying, that the dread of it stays with pilots for as long as they remain naval aviators. "There's some fear every time you're in the air, mixed with excitement and thrill and tension," Yogi says, "but a night carrier landing is the only thing that is sheer, unmitigated terror." You've done day landings on carriers back in flight school, of course, and practiced night landings on the silhouette of a flight deck painted on a regular runway. But nothing, nothing prepares you for what's coming next.

You are flying out of a black sky onto a black sea, and suddenly you see a dot of white light miles away in the void. The voice on the radio tells you that's the ship down there, but all you see is the little light you must follow down into the controlled crash that is a carrier landing in the best of times. If you are lucky the sea is calm and the air is clear, but if the light bounces in the dark you have no way of knowing which is moving, you or the ship. All you know is that somewhere down there is a 60-foot wall of steel and only 700 feet of deck. If you hit too low you'll have to be scraped in bits and pieces off the side of the ship, and if you come in too high and fail to snag the restraining cables with your tailhook you'll have to come around again - and you've already screwed up once.

The VF-1 Wolfpack was out on cruise in the Indian Ocean one particularly rough, dark night when a pilot had to come around twelve times. Twelve times. The poor guy had nowhere else to go, and he came around and around, burning so much fuel that twice tankers launched off and refueled him in midair and landed on the pitching deck while he was still out there trying to make it down. When he finally did, he hit the deck so hard that he damaged the plane, and when he climbed out of the cockpit he was crying and looked like an old man. "You never get used to it," says Organ, who sat up half that night watching his buddy trying to come back out of the sky. "If you do, there's something wrong with you."

By the fall of 1981 Yogi and Possum had finished their training at VF-124 and were assigned to their permanent squadron, the VF-1-the squadron they will fly to battle with in the event of war. For as long as they remain with the Wolfpack, it will be their home and family, security blanket and confessional circle. Possum's wife, Lisa, has already joined the Wolfpack's wives group, her family when Possum is out at sea, and in time she will realize that her husband will spend more hours of their married years with Yogi than with her. Indeed, shortly after Yogi and Possum joined the Wolfpack, they began training for a sea tour, and in a few months they were ready. Possum helped Lisa lock up the apartment and store their belongings, then drove her to her parents' home in Newport Beach, where she would stay for as long as he was at sea. And on April 7, 1982, the Wolfpack took off from Miramar and landed aboard the USS Ranger, already under way 100 miles south of San Diego. It would be six months before they'd be back.

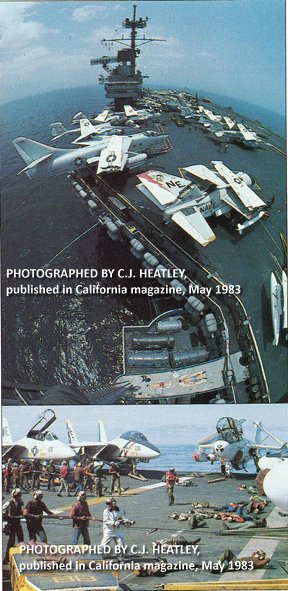

Top: With its four acres of flight deck, the USS Ranger can accommodate as many as 85 planes (their wings folded while parked) and two sunbathers. Bottom: In the mass casualty drill, the entire carrier crew enacts various worst-case scenarios, including nuclear attack. PHOTOGRAPHED BY C.J. HEATLEY.

Top: With its four acres of flight deck, the USS Ranger can accommodate as many as 85 planes (their wings folded while parked) and two sunbathers. Bottom: In the mass casualty drill, the entire carrier crew enacts various worst-case scenarios, including nuclear attack. PHOTOGRAPHED BY C.J. HEATLEY.

SPACESHIP DESIGNERS COULD USE the aircraft carrier as a model. With 5,000 men aboard, it is a floating steel city, complete with office suites, apartments, parking lots, and machine shops securely hidden under a deck so solid that a 25-ton plane can crash onto it and it won't even be felt below the main level. And as in any city, one can live and work for months and meet only a handful of people and never visit entire neighborhoods.

On Yogi and Possum's first cruise the Ranger stopped in Hawaii for a few days, then for four days in the Philippines, where several time-honored naval aviation customs were followed. A team was sent out to look over the wood-carving shops in downtown Manila and place an order for a new Wolfpack plaque to hang at the entrance of Miramar's WOXOF Room. Then the entire squadron was measured for snazzy new red-on-gray flight suits, which downtown tailors could whip up for only $27 each. By the time the Ranger stopped by again on its way home, everything would be ready. The next port was Singapore. There Gringo located a good-size brass bell that the Wolfpack would also present to the club when it returned.

But then the Ranger reached the Indian Ocean and stayed there for 101 days, and the fun was over. It finally dawned on Yogi that yanking and banking has a deadly intent. Naturally he knew that being a fighter pilot meant that someday he might have to go into real-life battle, but it wasn't something he looked forward to. "I'm no warmonger," Yogi mused one evening. "I don't care if we never go to war. The only thing is, if we do I'd like to be there." One day an order came over the carrier's speakers, and Yogi and Heater blasted off the deck like human cannonballs, their F-14s loaded to the gills with live ammo. Heading their way was a massive Russian plane that looked like a transport but could have been anything. As they escorted the plane away, Yogi edged up so close that he could look over and see the Russians in their cockpit, staring at him and snapping photographs. He waved the way one does when someone is taking pictures, but the Russians didn't wave back - not even when Yogi's backseater took their picture.

Yogi and Possum flew at least once a day off the Ranger, but most flights were ordinary patrols or exercises. There was little air combat, except when a few F-14 drivers would head out to a randomly selected "MiG alley" over the ocean and practice dogfighting. Years ago, legend has it, some of the men on a cruise would play other games, games they would have been drummed out of the navy for if they were ever caught playing. In the game of "thumping," a guy might be flying straight and level without a care in the world when another would come slinking behind and below, then shoot under him and go into a sharp climb right in front of his nose - not only scaring the living daylights out of him but interrupting the air currents around his wings.

Though Yogi would dogfight with the best of them, he was almost too serious for the Wolfpack crowd, and he tried to use those long ocean flights to improve his flying skills. "He was like a sponge, soaking it all in," says Heater, once an instructor at Top Gun and Yogi's instructor on the cruise. They spent hours talking tactics in the briefing room before and after missions and in the dining room during meals, and then Heater began teaching Yogi classic air maneuvers such as the "vertical egg," in which two planes chase each other in ever-widening vertical loops. And while Yogi was learning from Heater, Possum was doing the same sitting behind Gringo.

Finally, after more than three months in the steaming Indian Ocean, the Ranger started to head home. The first stop would be Perth, Australia, and the Wolfpack was determined to do it in style. Few of the men knew how or when Gringo had planned it, but no sooner had the Ranger dropped anchor than a glorious sailing yacht materialized alongside with a huge sign on its mast: WELCOME WOLFPACK. When the VF-1 gang got on board there were bottles of chilled champagne waiting, which they hoisted in full sight of the poor suckers still waiting to hitch a ride to shore.

The first thing Yogi did when he got in was pull out a phone book, call up a couple of skydiving clubs, then head out with them to do some free-falling. Possum and a few of the others rented a car and went sight-seeing. Before blowing town, however, the Wolfpack organized a bash. The invitations-engraved - went out to every city official in Perth they could think of, as well as to the other fighter squadrons. That, everybody had to admit, was class.

But nobody expected class at Subic Bay near Manila, where the Ranger then stopped for five days. Sometimes it seems that the only reason the Cubi Point naval base was built there, with its officers club high on a hill overlooking the bay, was to give naval aviators back from a cruise a place to let off steam. Anything goes, including, after enough beer went down one evening, pushing all the tables together in the shape of a carrier deck, stretching a few towels across, and doing belly landings. Somehow somebody remembered to pick up the new Wolfpack plaque and the custom-made red-on-gray flight suits, and even to have Gringo's big brass bell mounted on a specially engraved base.

Delivering the bell to the WOXOF Room was a great event. It was no ordinary bell. The Wolfpack had brought it for a purpose, to help uphold the club's bylaws, which state that a bell should be rung on two occasions - when someone walks into the club with his hat on, or when a customer finds himself behind the bar. On either occasion, the transgressor picks up the tab for everybody's drinks. Of course, to hang the bell the Wolfpack had to get behind the bar, but what the hell- the going was still first class.

Shortly after they returned to Miramar, Yogi and Possum were assigned to fly together. They had done well separately on the cruise, and even better once they became a team. In fact, they did so well together that last January they were told to report to Top Gun for air combat training. Now they would learn what being a fighter pilot is really all about.

IF WAR BROKE OUT AND THIS country's aviators were ready for it, it would be a first, and the credit would belong entirely to Top Gun, located in a second-floor cubby of offices at the east end of Hangar One at Miramar. There is history on the high walls that flank the pipe-railed stairway - they are covered with red stenciled silhouettes of MiGs shot down in combat by Top Gun graduates. For a young fighter jock swaggering up the stairs in a brand-new flight jacket, the effect is awesome. At the top of the staircase are two large silhouettes stenciled in black. They are two Libyan SU-22 jets bagged in 1981 over the Gulf of Sidra by two F-14 crews from the USS Nimitz, and the only air kills since the Vietnam War.

In 1964, just as Yogi and Possum were entering the third grade, North Vietnamese gunboats fired on the U.S. destroyer Maddox in the Gulf of Tonkin (or so President Lyndon Johnson insisted), a war flared up, and suddenly hotshot naval aviators were getting creamed by Charlie pilots who were just learning how to drive their early model MiG-15s and -17s. The navy was losing one Phantom for every two MiGs it bagged. A 1968 study commissioned by the navy concluded that the problem was missiles that didn't work and aircrews who didn't know how to dogfight, and it recommended the establishment of a fighter-pilot school. In reality, the whole thing was a monumental Pentagon screw-up. The navy's brand-new, high-tech F-4 Phantoms were designed, and their pilots trained, to intercept high-flying Soviet bombers – to scramble up, locate the target on the radar, nail it from behind with a missile, and come home. Easy. But confronting those fast little MiGs was something else.

In the spring of 1969 a few crack flight instructors with VF-121, the F-4 Phantom training group at Miramar, got together in a small trailer outside their hangar to establish the U.S. Navy Postgraduate Course in Fighter Weapons Tactics and Doctrine. In time it would be renamed the Navy Fighter Weapons School, but it was Top Gun - the name of an annual air-to-air gun competition held by the various armed services in the 1940s and '50s - that stuck. Inside the trailer were two tiny offices, a narrow hallway, and a room into which the first class of eight could barely fit, but it was the birthplace of a revolution in fighter aviation. For the first time fighter jocks – not Pentagon experts or plane manufacturers – were setting performance standards for their flying machines. There were long debates into the night. New air maneuvers were invented, first with hands tracing loops in the air, then on the blackboard, and finally, the following morning, in the skies.

They started by flying F-4 Phantoms against F-8 Crusaders, the Navy's last classic single-seater fighter, and then against Mongooses, stripped-down A-4 Skyhawks that made great MiG imitators. By the time the air war over Vietnam was resumed in early 1972 after two years of inaction, scores of Top Gun graduates were out on their carriers off the coast and MiGs were being shot down all over the place. The navy's kill ratio zoomed to twelve to one. But the final seal of approval on the Top Gun concept came on May 10, 1972, when two recent graduates, lieutenants Randall ("Randy") Cunningham and William P. ("Willy") Driscoll, blasted off the USS Constellation and headed toward Hanoi to escort an attack force over the Hai Dong railroad yards. It would turn out to be the hop to end all hops. Not just because they downed three MiGs in one day, but because those three took them over the magic five-kill line to make them the first official aces of the Vietnam War. As the navy flew Randy and Willy home to parade them across the country, the story of that little hangar at Miramar finally started getting out, and when the war drew to a close combat-seasoned jocks scrambled to get there as instructors.

To truly appreciate what was happening at Top Gun in those heady years of the early 1970s, one must first understand that there are few caste systems as elaborate and demanding as the one military pilots live under. Its dividing lines are drawn like the circles around the bull's-eye of a gunnery target. On the outside is the mass of humanity that doesn't count at all nonflying nonentities. In the outer ring, only slightly more significant, are the aviator's families, groupies, and hangers-on. Then come helicopter pilots, transport pilots, bomber pilots, and assorted prop-driven plane pilots, and next the attack pilots, whose planes have no afterburners and who charge at ground targets only. In the inner rings, where fighter pilots belong, there are finer distinctions that only the pilots themselves can discern, until one tiny circle is left at the center, the bull's-eye, where the elite of the fighter elite stand in glorious isolation. The greatest of the greats, the makers of legends – the "shit-hots."

At Top Gun, back in those postwar days, everybody was hot. So hot that the place sizzled even when nothing was happening. So hot that a lot of people suggested that even Randy Cunningham didn't truly belong there. Not that he wasn't a great fighter pilot. His three-MiG day was awesome, and in 1976 he and Willy Driscoll would actually be inducted into the base's Aviation Hall of Fame. But, though the young aviators at Miramar might be content to gape at Cunningham's two silver stars and Navy Cross, to the Top Gun hotshots his new MIG ACE license plate was, well, unprofessional. "Really great fighter pilots are like the great gunfighters in the Old West," says Jim ("Hawkeye") Laing, one of the original Top Gun hotshots. "They didn't have to tell anybody how great they were - all they had to do was just stand there, and the aura was such that everybody knew. It's the same here. Everybody knows."

Not that anybody was just standing around at Top Gun. There were the drinking sessions at Bully's, a steak house in San Diego, and the late-night car races in Imperial Valley, running through sleepy little towns at 100 miles an hour with no headlights. "It's all right, officer, we're from California," a tanked-up marine hotshot once told a cop who had stopped him. "This is California," the cop answered, and wrote him up. But most of all there was flying. Glorious flying. The greatest fighter flying in the world was taking place every day over Yuma, Arizona, or the Chocolate Mountains or the Pacific Ocean as Top Gun's Vietnam vets set out to rewrite every single fighter aviation text ever written.

Yet this fighter pilot's Valhalla almost came to an end in late 1977, when Rear Admiral Frederick ("Field Day Fred") Fellows assumed command of Naval Air Station Miramar and set out to restore discipline and naval decorum to the fighter community. Suddenly the old peacetime regulations were being enforced, and before long the hotshots began to leave. Top Gun's dark ages lasted until the spring of 1979, when Fellows was replaced by Rear Admiral Paul ("Gator") Gillcrist. Unlike his predecessor, Gillcrist was a fighter pilot's pilot - he had flown the F-8 Crusader in the early years of the Vietnam War. A sigh of relief swept the fighter jock community, but by then so many of the original hotshots had left that hardly anybody with any war experience was available for a Top Gun instruction post.

By the time Yogi and Possum walked over from the south end of Hangar One, home of VF-1 Wolfpack, to the north end to begin their Top Gun training last January, only the course chief, Commander Ernie ("Ratchet") Christensen, and one or two instructors could speak with the authority of actual combat experience. But it was still shaping fighter aviation doctrines and tactics, and it was still the greatest fighter-pilot school in the world.

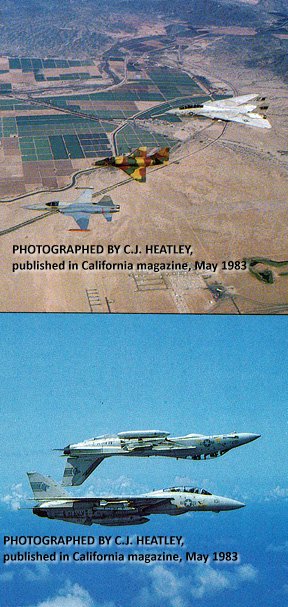

Top (left to right): An F-5E Tiger II, an A-4 Skyhawk painted in camouflage, and an F-14 Tomcat head home after dogfighting over Yuma, Arizona. Bottom: Two F-14 pilots demonstrate the agility and grace of their 25-ton monsters in a classic Blue Angel “back-to-back” maneuver. PHOTOGRAPHED BY C.J. HEATLEY.

Top (left to right): An F-5E Tiger II, an A-4 Skyhawk painted in camouflage, and an F-14 Tomcat head home after dogfighting over Yuma, Arizona. Bottom: Two F-14 pilots demonstrate the agility and grace of their 25-ton monsters in a classic Blue Angel “back-to-back” maneuver. PHOTOGRAPHED BY C.J. HEATLEY.

IT STARTED SLOWLY, GENTLY. There were lectures and briefings, but soon Yogi and Possum were up in the air, and there was more flying than they had ever had. There were one-versus-one hops (one student crew against one instructor), then two-versus-two hops, and then came the tough two-versus-unknown hop, in which two student crews take off not knowing how many bogeys are waiting out there or where they'll come from or in what order. That's how Yogi and Possum happened to be flying off the coast of Ensenada on that bright January morning, just floating through the blue looking for game, when that F-5 rolled in and sent them home with a simulated Atoll shot. Before long the hops were running into each other, and Yogi and Possum noticed that something was happening to them. They were flying twice a day - not cross-country cruising but edge-of-the-seat, hard flying, intense, mind-bending flying- and they didn't even have to speak except to draw attention to a bogey. They were being hammered into a team.

And so it was that on a sunny day last February Yogi and Possum strolled out of Hangar One in their flight suits, with their helmets and oxygen masks dangling from their arms and their chutes slung macho-casual over their shoulders. Their plane was ready and waiting, and as they climbed into the cockpit nobody came running up to say that the hop would be delayed. That was a good sign right there. And then the little huffer cart blew air into the engines to get them going, and in seconds their machine was humming like a rocket. They taxied out to- the runway, lined up, and blasted off, and still everything was okay. They banked right and leveled off at 2,000 feet, then climbed higher and headed for the rugged Mojave Desert country around China Lake for the most important Top Gun hop, the culmination of their training. It was a great beginning for a great hop.

Once over China Lake they teamed up with a few A-7 attack planes, which they escorted over "enemy" land on a bombing mission. The A-7s did the bombing, and Yogi and Possum and the rest of the F-14s went along on a MiG sweep, looking for bogeys and fighting their way to and from the target area, taking care not only of their own tails but of those nose-down A-7s below. Since this was "enemy" territory, and the Russians were big on radar control, they flew in low, hugging the terrain at 500 feet.

Yogi and Possum were zipping along, shooting up mountains and down canyons and flying so low that it was hard to keep from staring at the ground, but they had to keep looking for bogeys. Only a few days earlier they had been out there over China Lake, just coming out of a mission, when they turned back and saw two bogeys riding their tail. Yogi watched the one on the left and Possum tried to keep the one on the right in sight, but then Yogi found out that his bogey had just fired a missile. There are a couple of things a pilot can do with a heatseeking missile heading his way, and one of those is to break hard - pull away fast - to foul up the missile's tracking system. Possum was losing his bogey and was just turning his head to look over his right shoulder when suddenly Yogi pulled the stick and headed up in a 7.5-G climb. As Possum fought to keep his face from smashing into the radarscope he heard his neck begin to pop, the vertebrae cracking the way knuckles do when pulled – "puk, puk, puk." That’s when Yogi said real cool into the mike, "Hey, you still got those guys back there?" Possum couldn't even look up to ask him if he was kidding or what.

So now they were shooting up and down those brown and yellow desert hills, and they still had to keep an eye peeled on that huge blue dome above them. But nothing happened. They saw a few bogeys in the distance, but nothing to worry about, and they came over the target area and turned around and headed back, and still nothing. They would have preferred a little more action, when you came right down to it, but what really mattered was that they had been ready for it all along- they could have fought their way out of anything. They had made it into bogey country and hadn't screwed up once.

Yogi and Possum finished the Top Gun course at the end of February. As their class picture went up in the briefing room and they received their new Top Gun flight jacket patches (a MiG caught in a fighter's cross hairs), the news came that the Wolfpack was named top fighter squadron on the West Coast-one of only two contenders for the Admiral Clifton Award, the navy's greatest tribute to a fighter squadron. Two weeks later the men of the Wolfpack began flying out to land on the pitching and rolling flight deck of the USS Kitty Hawk, some 100 miles out to sea off San Diego, in preparation for their next cruise. This time Yogi and Possum would lead those long fighter patrols over the Indian Ocean, and out there over their wing would be a young pilot just out of training, eager to learn how to be a real fighter pilot.

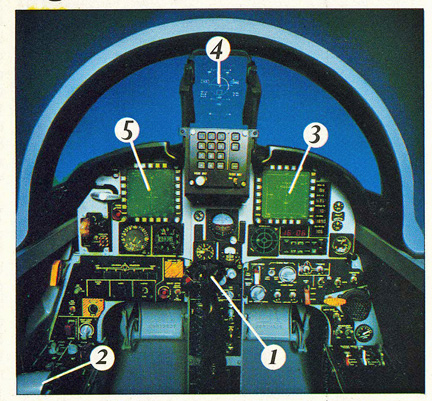

Sidebar: DREAM MACHINE

Step into the Tigershark-the ultimate video game.

SUPER ACE CHUCK YEAGER, the first pilot to break the sound barrier, once said that "of all the airplanes in the world that I've flown, the F-5 is the most fun to fly." The F-5 is actually a family of planes, starting with the F-5A back in 1964 and culminating last year with the F-5G Tigershark (now called F-20). All are elegant, zippy beauties with body lines so trim they look like canoes with wings. The only fighter plane made in California, the F-5 is an anomaly in the high budget defense business. It is not only small, effective, and easy to repair, but it is also very cheap. The F-5E Tiger IIs used by Top Gun instructors to simulate Russian MiGs cost around $5 million each, and even the top-of-the-line Tigershark lists at only $9 million -- one quarter the price of a single F-14 Tomcat. The navy could court-martial anyone it caught showing off the classified cockpit of the F-14, but here's how to make a hop in an F-20:

1. The stick. Say you're entering bogey country. To find out what's ahead, push the air-to-air weapon select button with your right thumb. (This is basically an "on" switch-your head-up display and digital display indicators are now operating.)

2. The throttle. With your left index finger, select "range while search." A plot (which looks like a radarscope) of the range in question will appear on your right-hand digital display indicator.

3. The right-hand digital display indicator. If there's a bogey out there, it will appear on this screen as a small black square. To lock your radar onto its tail, press the throttle's acquisition button until the screen's acquisition symbol (two parallel vertical lines) brackets the target. Suddenly the acquisition symbol disappears, and a numbered aiming circle appears around the black square - this tells you at a glance how fast, how high, and in what direction the bogey is going.

4. The head-up display. From this point on, you can look straight through your head-up display and see both the real target and the head-up steering circle (which looks like a bull's-eye) simultaneously.

5. The left-hand digital display indicator. On this screen is a list of your available missiles and gun ammunition. Once you have picked your weapon, maneuver the plane until the head-up display's steering circle is directly over your target. When you reach the proper range the word SHOOT will flash onto your head-up display. Pull the stick's missile release or gun trigger with your right index finger. Bingo.

Sidebar: THE AGONY AND THE AGONY

The truth behind yanking and banking.

IF YOU SIT IN THE COCKPIT OF AN F-5 AND DROP YOUR hands to your sides, your fingers reach two metal bars lying flat along the base of the seat. The bars are painted in black and yellow stripes - a warning sign. Pull up and squeeze them and an explosive charge will blast you out of the cockpit and into the air, your seat will drop away, your parachute will open above, and you will float safely down to earth. That's how the ejection seat is supposed to work if anything goes wrong with the plane, but the trouble is you can't practice with it, only memorize a series of steps. "How many times have you punched out [ejected]?" asked Lieutenant Al ("Shoes") Mullen when I told him I wanted to run through it all again before our flight.

"Not once," I said.

"That's as many times as I've done it," he said, "and I don't plan to start now."

In a crazy sense, there was more reassurance in that fighter jock's swagger than in all the hours of safety training I had completed before going up in an F-5 (F-14s are classified - no civilians allowed) with Shoes as my pilot.

It was raining on the morning of our flight, but then the gray cloud cover broke, and taking off and flying through those fluffy white clumps was a near-sexual delight. It didn't last. As we flew over an Imperial Valley date farm and began dogfighting with Yogi and Possum in their F-14, my dispassionate observer mode was brutally shattered. It began as Yogi and Possum drifted away, vanished, then turned and headed back in our direction. Suddenly Shoes whipped the stick hard, first to the left and then to the right, and before I could catch my breath or brace myself he must have seen something, because he pushed the throttle and sent us into a sharp climb. It was my first introduction to the G forces.

When you are pulling Gs - withstanding several times the force of the earth's gravitational pull- the pressure comes from everywhere. Even your eyelids weigh several times what they normally do, and the pressure on your chest is so intense that you can hardly breathe. For the next half hour or so, I learned later, we went through several classic air moves, but all I remember is a series of flash impressions and a general feeling of physical torture. The things I thought would be the hardest to take, such as flying upside down, were anticlimactic. Indeed, at one point I remember seeing green fields where the sky ought to be, and it was sheer nirvana - after several minutes of pulling Gs and feeling the air pockets in my G-suit inflate against my legs to force the blood back to the heart, it was a relief to rest head down and let the blood return to my brain. And then, in an instant, we were climbing at 6.5 Gs, and I realized I was sitting slumped in my seat like a shriveled old man, a 1,100-pound old man, unable to straighten my back.

There were a lot of things I was unable to do. I couldn't pick up my camera from a nearby shelf-on earth it weighs about one and a half pounds. I couldn't slow the plane by pressing my feet forward as Shoes suddenly pointed the plane nose down and went into a dive. I couldn't keep track of Yogi and Possum's plane, streaking by like flashes of metallic light and nothing more. I had never, felt so useless in all my life. I had lost control of everything that was happening from one second to the next, exactly the opposite of what fighter pilots feel – and must feel – all of the time.

And when I climbed out of the cockpit at the end of our hourlong flight, I couldn't even swagger. Every muscle in my body ached, I was exhausted and slightly nauseated, and all I wanted to do was go to sleep. But they tell me the first time is the worst, and I can't wait to get up there again.

A third sidebar related to former fighter pilots living in San Diego is not presented here.